How To Make Video Learning More Effective: 4 Easy Ways to Communicate Better

Get your ideas across in a way that people remember

This week, one in three people has watched an educational video. Given that you’re reading an article about learning, I’m guessing you’re one of them.

When French inventor Louis Le Prince filmed the first ever video in 1888, he painstakingly put a 2 second video on paper-based film at 7 frames per second. Less than 150 years later, 90% of the global population has access to a device that films 1000s of hours in crystal-clear pixels. Video learning is here to stay, but its not without its problems - if used correctly, videos are the among the best ways to teach people; if not, they’re part of the widening gap in education caused by the pandemic.

If you’ve ever wondered what makes a good video, I’ve dived into the research to find some easy but effective ways to get started.

1. Keep it under 6 minutes

Really.

There’s a 10% drop in correct answers about the last half of a lecture. As watch time increases, the number of people losing focus almost doubles: the shorter you make something, the more likely it is that someone will give it their full attention.

There’s no concrete answer to “how short” because it depends on the type of content. As a rule of thumb, most viewers want instructional videos between 3-6 minutes (going up to a maximum of 20 minutes). Not only does help people remember more, it also forces the creator to really narrow down what’s important and what isn’t. However, this doesn’t mean that you can’t make in-depth content: instead, break the video into 6-minute chunks by concept, which will have a similar effect even when the viewer doesn’t have to actively click on the next part.

2. Don’t make it flashy

If it’s simple, it’s easy to learn.

Get rid of interesting but non-essential content.

Remove subtitle text when teaching native speakers.

Don’t use graphics when they aren’t needed.

All of these help us focus on the stuff that matters.

But be careful with how far you go: entertaining content can make you emotionally invested and so more focused, while subtitles are incredibly useful for second-language learners. In a video teaching patients about a surgical operation, 3D animations helped a lot. But in another video about the science of lighting, 3D animations distracted viewers and made them learn less.

3. Interact with your audience

Don’t you think it’s better this way?

Adding tests in between video clips gave an 18% jump in average final scores compared to students who revised between lectures: this rose to 40% when compared with people who didn’t revise at all. Make your viewers think, and they’ll not only pay more attention, they’ll also remember far more.

Simply getting viewers to do something also helps: adding an interactive platform and the ability to skip between slides boosted mean test scores over 20% and even made users happier.

The more engagement you have with a video, the more you can learn.

4. Talk to Me

You’d much rather learn from a friend than some monotone robot.

Even in a video, you learn better when it seems like a conversation. Something as easy as changing “the” to “your” had a noticeable impact on learning, and using more personal pronouns (I, you, we) sparks a social connection, even when there’s a screen on the other side. Something weird happens when our body tells us we’re being social, and this still kind of works online.

A small change in tone or content can have a massive impact on what a viewer takes away. Many things can’t replace an in-person chat or a good book, but using the tools you have it’s possible to resonate with a far greater audience than ever before. If you decide to use video, make the choice to communicate better a deliberate one.

Thanks for reading! If you’re still interested, I’ve included some less well-backed (but still interesting) methods researchers have tried in the sources:

Sources

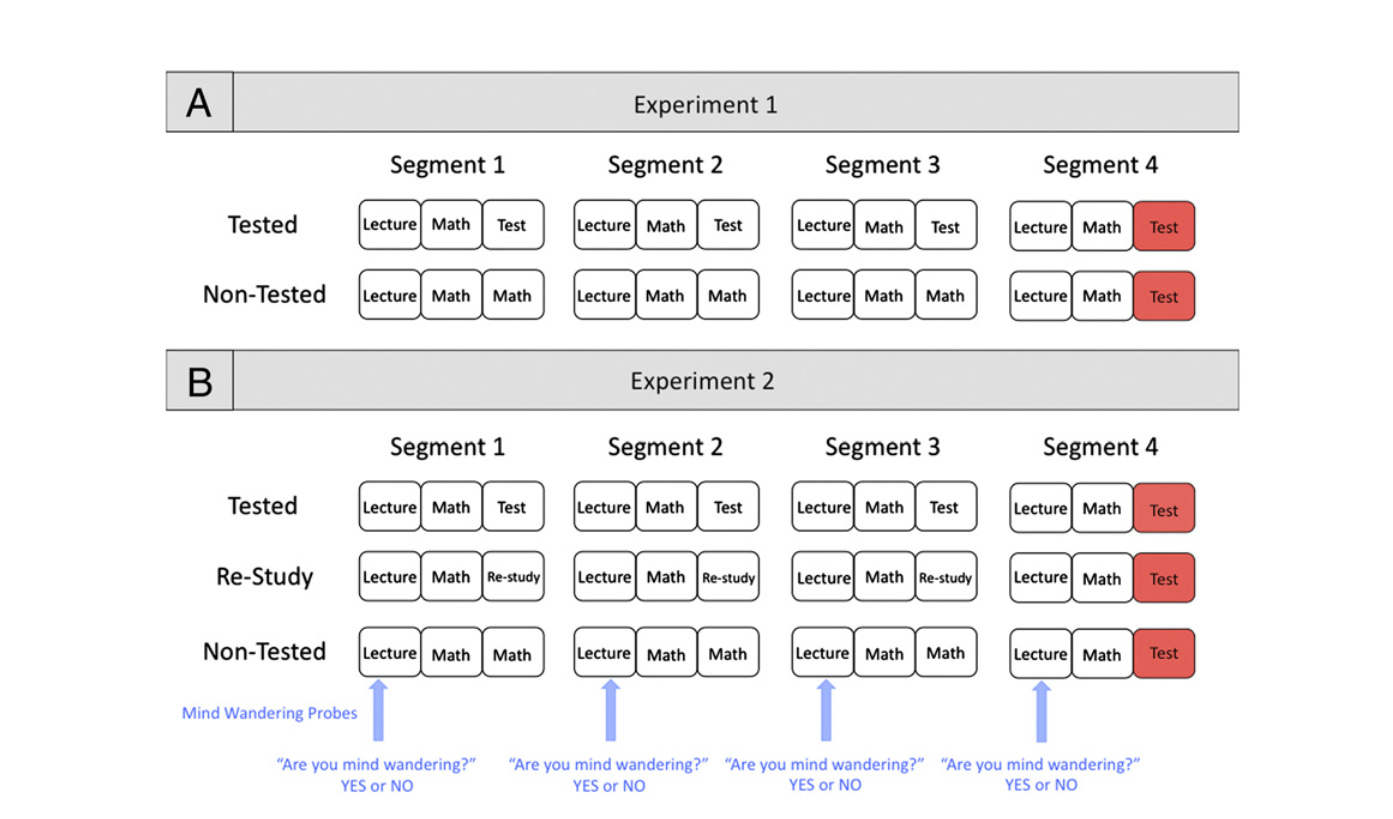

Interpolated memory tests reduce mind wandering and improve learning of online lectures (pnas.org)

(2013, Journal Impact Factor - 12.8)

80 students over two experiments. 40% increase in test scores immediately after last lecture when compared to non-tested. Around half the rate of mind wandering and students were less anxious about the final test, with an average score 18% higher in final test than students who did revision in the same periods. “Taken together, the present results demonstrate that interpolating an online lecture with testing can help students to quickly and efficiently extract lecture content by reducing the occurrence of mind wandering, increasing the frequency of note taking, and facilitating learning”.

Five ways to increase the effectiveness of instructional video | SpringerLink

(2020, Journal Impact Factor - 3.6)

Evidence-based examples instead of comprehensive review of literature. The studies referred to are listed below. These studies mostly use Cohen’s d effect sizes (standardized mean difference between two groups of observations) - this measure has been criticized for being “arbitrary”.

Dynamic Drawing: study shows people learn better from a video lecture when instructor draws graphics as they lecture instead of using pre-drawn graphics. Note that this benefit did not work when the video did not show the instructor’s hand doing the drawing, nor on more knowledgeable participants. Signaling principle (showing where to look), segmenting principle (breaking graphic into smaller segments), temporal contiguity principle (coordinating visual and verbal aspects of the lesson).

Gaze Guidance: when instructor moves gaze between whiteboard and audience, in particular when using a “transparent whiteboard”, there was better performance on a test immediately after the lecture. (But insignificant difference on a delayed test). Another study showed better performance on a transfer test with a similar setup.

Generative Activity: Idea that making notes summarizing video content can help later test performance. Interestingly, a different study found that students not taking notes did better on “near-transfer”, while students who generated notes did better on “far-transfer”, essentially being able to do more broad-based application of the knowledge.

Perspective Principle: Students did better on tests after a demonstration filmed from the first person perspective.

Subtitle Principle: For native language speakers, subtitles don’t really help, but for second language learners they are useful.

Seductive Details Principle: Too many effects may distract learners. College students did better on a test when the lecture did not have lightning storm clips interspersed.

Studied 78 college students, split 22-19-21-16 for no-text, no-seductive → text, no seductive etc. Only considered students who scored below 7/11 in initial test. Note that the text was a summary of what the narrator was saying, instead of direct subtitles. Seductive details in this case were fun facts about lightning.

Follow-up experiment testing no text, summary text, subtitle text, 109 students.

Experiment 3: 38 college students to test whether adding clips of lightning that are “surface” related would affect learning. Results not significant enough to decide.

Experiment 4: 32 college students test whether interesting clips before/after helped learning because of emotional investment. No statistically significant result.

(2018, Journal Impact Factor - 2.4)

The effect of educational videos on student activity and learning as documented through peer-reviewed empirical research in psychology, education, and learning analytics from 2007 to 2017. Focused on higher education, professional learning and MOOCs.

“The conclusions are drawn from the in-depth analysis of 196 unique studies reported through 178 peer-reviewed papers”

“Modality affects how much content students remember.”

“Using captions is redundant for native speakers, but greatly improves recall when learner language proficiency is taken into account.”

“Manipulating video presentation has significant effect on learner attention and student satisfaction.”

Mixed results on animation - depends on situation, e.g. for an operational process 3D animations were helpful for remembering demonstration, but in biology learner understanding of cells, 3D animations less effective than text-based schematic visualizations: learners overwhelmed.

“Manipulation of video content has significant effect on how students transfer learnt information, and on information recall.”

“These studies report an association between video viewing behavior and higher achievement; such a finding has been similarly reported in MOOC contexts.”

“Our preliminary analysis suggests that immediate quizzing and clearly presented information helps learners recall video content. However, more compelling ways of offering content that can challenge prior knowledge or present problem solving activities can impact overall long-term understanding, even though this may not be ideal for recall.”

(2016, Journal Impact Factor - 3.3)

Cognitive load - studied elsewhere but literature lacks purely video-related research on this topic.

Recommendations:

Keep videos brief and targeted on learning goals.

Use audio and visual elements to convey appropriate parts of an explanation; consider how to make these elements complementary rather than redundant.

Use signaling to highlight important ideas or concepts.

Use a conversational, enthusiastic style to enhance engagement.

Embed videos in a context of active learning by using guiding questions, interactive elements, or associated homework assignments.

(2011, Journal Impact Factor - 4.7)

226 undergrad students. Half got a standard video, the other half got a video segmented into 5 conceptual segments (built-in, students had no control over sequence or playing/pausing). Used signaling - introduction with title and core concepts as a narrated bulleted list. Summaries presented at the end. Weeding performed to get rid of sections that were entertaining but not essential for content understanding.

“Nevertheless, the finding that the test scores for the SSW [segmenting, signaling, weeding] group were significantly higher on all measures of learning demonstrates that the SSW intervention did improve learning outcomes for domain novices learning from dynamic audiovisual materials, accounting for as much as 8% of the variance in knowledge transfer.” (3.1% overall knowledge, 3.2% knowledge retention, 8% knowledge transfer) (2.3% decreased perception of learning difficulty).

Save cognitive resources for processing essential content.

(2006, Journal Impact Factor - 7.6)

138 students on effectiveness of LBA (learning by asking) multimedia system. Lectures presented alongside slides, and learners can click “next” to skip slides or jump to any part of the lecture content index. “The tests supported our hypotheses on the positive effects of interactive video on both learning outcome and learner satisfaction in e-learning. Students in the LBA group with non-interactive video achieved equivalent test scores and levels of satisfaction to those in the e-learning group without video. This implies that simply integrating instructional video into e-learning environments may not be sufficient to improve the e-learning effectiveness.”

(2011, Journal Impact Factor - 1.6)

60 students asked to watch a 60-minute lecture, prompted at 5, 25, 40, and 55 minutes into the lecture as to whether they were mind wandering. Participants were more likely to answer correct when questions were from the first half (71%) compared to the second half (59%). The more someone mind wandered, the worse they did on the test (77% - 54%).

Second experiment involved 35 students, video lecture presented in a classroom setting.

“Taken together, Experiments 1 and 2 strongly demonstrate the existence of an increase in mind wandering with time on task in a lecture context and the potentially associated deleterious effects on memory for the lecture. The reported patterns appear to rest on solid ground despite the small number of probes used.”

The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning - Google Books

(2014)

Personalization Principle: using first person (I, you) and directly making comments to the learner. Even small changes such as changing “the” to “your” had benefits to learning. Effect size ~0.8.

Kind-of related resources

(2017, Journal Impact Factor - 3.34)

Narrow focus on in-service teacher professional development. Note this is a scoping review, instead of a systematic one. Most focused on teachers reviewing content such as classroom observations or peer coaching.

Teachers who analyzed their own teaching had “higher immersion, resonance, and motivation”. In combination with watching other styles of teaching/coaching, there is better self-confidence, self-evaluation, knowledge (new techniques, collaborative reflection), and more positive disruption of previous beliefs.

Video could be a good chance to improve professional learning in low-resource schools. However, high quality support is needed as pure video viewing may not be effective. In addition, 53 of 82 studies are entirely qualitative, meaning more quantitative research is needed to confirm the magnitude of improvements.

(2015)

A series of interviews with experts about the use of online teaching. Offline teaching is very different from online, especially because teachers cannot respond to real-time situations in the same way. Video should be a conscious decision instead of a default option, and a DIY approach is often more effective, suggesting that teachers need training in media tools.

(2009, Journal Impact Factor - 1.4)

Points out the need for more flexibility and learner interaction in online courses, especially to promote the social effect. Tutors would need special training to encourage discussions online. Case studies were particularly useful in making coursework directly applicable to the professional environment.