The Neuroscience of Meditation

How does our brain physically change after mindfulness meditation?

Meditation used to border on psuedoscience for me. Enlightenment, transcendance, or “finding inner peace” put me off it for a long time.

It’s a shame, because there’s a huge amount of great “real” science being done on it

At the same time, even the academic research is flooded with studies that haven’t been replicated, have poor methodology, and have arbitrarily drawn conclusions. A meta-analysis shows that there is a relatively strong bias towards publishing positive results on this topic, which means we tend to only see the good outcomes.

Of course, mentioning these limitations doesn’t make for good headlines, and methodological weaknesses seem to be completely ignored or swept under the rug when meditation comes to our attention.

I’m still a fan of meditation, and precisely because of that I believe that it’s important to clarify what exactly we know and don’t know about it.

The clearest starting point is to take a look at physical changes in our brain structure, which we can then link to its effects.

What is meditation, exactly?

The word meditation covers such a wide range of things that it’s almost impossible to fully study: there’s stuff on training mental visualization, deepening compassion, or even just going on a spiritual journey.

Here we’ll focus only on meditation for mindfulness,

“Awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally”.

Any further mention of meditation here is about a type of attentional training that allows you to be more aware of your own thoughts.

Based on traditional Buddhist practices, mindfulness meditation was first developed as a clinical treatment in the 1980s, first stripped of its religious context and then adapted for western culture. Through training, you learn how to monitor and even regulate your own emotions and attention.

Meditation changes your brain

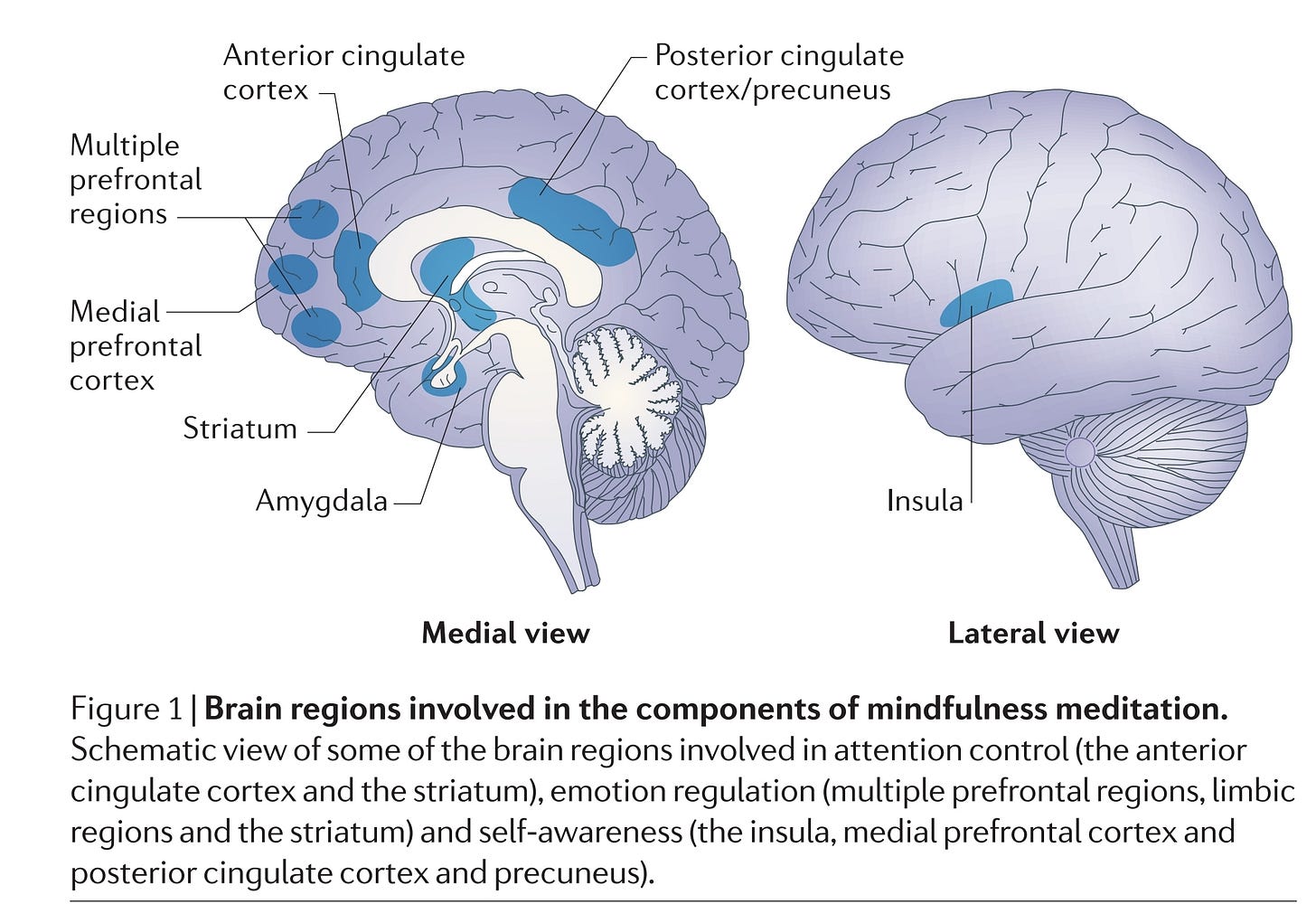

It’s pretty well established that meditation does physically change your brain in some way. Studies cover a wide range of methods and measurement criteria, so it’s not surprising that they find differences all over the place, not only in the different regions of the brain but also which parts of these are changed.

To make sense of this, reviewers used something called an “activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis”, which basically tries to find the most consistently changed regions of the brain across “good” studies. Here’s what they found:

If, like me, you’re not a neuroscientist, here’s a summary in plain english.

Better attention

Brain regions relevant to attentional control show “functional and structural changes” after mindful meditation.

For example, in Zen meditation practitioners, there was less decline in brain grey-matter as they aged, which went alongside better sustained attention performance. There’s also increased activation in the related areas across multiple studies.

Meditating improves your ability to pinpoint the information you need when exposed to multiple sources.

It also seems to help you regulate your response to conflict - this effect has been found after a period as short as 5 days. There’s also a long-term improvement in alertness, which only comes after months/years of meditation.

Better emotion regulation

Mindful meditation leads to decreased activation of the amygdala (the part that deals with fear) in response to emotional stimuli. Changes in this area are correlated with improving anxiety symptoms.

Although this structural change is common in meditation beginners, it’s actually not found as much in experienced meditators.

The theory goes like this: when you’re starting out, you actively regulate your brain activity to overcome your habits of reacting to things - top-down control gives you the benefits of better emotional regulation.

In contrast, once you’ve done this for a long time, you don’t need to rely on top-down control. Instead, you’ve fundamentally changed how you process things.

Brain regions related to motivation and reward processing also show changes - while resting, there’s more activity in the reward centers. The opposite is found when anticipating a reward: experienced meditators are probably less motivated by external incentives.

Better self-awareness?

This idea of self-detachment is potentially a massive benefit of meditation. For now though, a lack of evidence means that the connections we draw here are on shaky foundations.

Mindfulness does seem to be linked with higher self-esteem and self-acceptance, as well as an understanding into the impermanent nature of mental states.

There’s some evidence about better control over a region called the “default mode network” in meditators. This is responsible for self-referential processing, which is where we relate outside information to something about ourselves (so less of this means a more detached and objective view of external events).

Meditation also seems to make us more likely to be more aware of the present moment. Some studies show that during an emotional experience, meditators remembered facts much closer to the objective truth than others.

However, these are still preliminary results - as with most things, we need much more research to verify them.

How about the other stuff?

There are a huge amount of studies on meditation, and we can’t cover them all in one article. In short, this is what I’ve found:

Mindfulness meditation can help significantly with anxiety, depression, and emotional regulation.

It also has benefits in treating sleep disorders.

It doesn’t seem to be any better than other proven treatment methods.

Some people do find worsening effects as a result of meditation.

If you’re interested in a more detailed breakdown, drop me a message or leave a comment!

Limitations

Yes, this isn’t an academic paper where I have to list out the flaws in the findings, but just for completeness it’s important to at least mention some things to watch out for. The findings I discuss above are based on studies that follow good methodology, but even so we need to clarify three things.

First, meditation as a field of study in clinical settings is actually quite young, so we still need more time to verify causality in a lot of these theories.

Second, a lot of the differences we see for long-term effects of meditation are done through cross-sectional studies: basically, at a certain point in time we take people who have done meditation for a long time and people who haven’t, and compare their brains.

We can’t really be completely confident about the effects of meditation on the brain, because, for example, people who originally had a different brain structure might be more likely to do meditation - this isn’t accounted for in a cross-sectional study.

To verify causality, we now have more longitudinal studies - where you take a bunch of random people and monitor how their brain changes over time - but going back to the first point, these take a lot of time and money.

Third, and probably most importantly, the brain is way more complex than we initially thought. This means that we rely on things like self-reporting to match certain brain patterns with behaviors, but also that just looking at structural changes isn’t a perfect explanation.

Do these changes actually cause better effects? It seems like it, but again we need more longitudinal, randomized studies to be sure.

With all these in mind, it’s obvious that there’s still a long way to go; but we can also appreciate just how far we’ve come in investigating these things. Meditation is promising and has rightly gained a lot of hype, but there need to be clearer limits on what it can and cannot do.

I hope this can act as one point of reference to focus on.

If you’re interested in my sources, this article was mainly based off these systematic reviews, ranked in order of importance.

2015, Journal Impact Factor - 38.8

2017, Journal Impact Factor - 11.6

2014, Journal Impact Factor - 9.0

2016, Journal Impact Factor - 9.0

The neuroscience of meditation: classification, phenomenology, correlates, and mechanisms

2019, Journal Impact Factor - 2.6